Tropes Exemplified in Works of Art 8: Allegory

by Mark Staff Brandl

This week, I am continuing my short series of artworks exemplifying major tropes. This is the eighth entry.

The list of major tropes to which I am referring, I published on this website a while ago, “A List of the Most Important Tropes and Their Definitions”; here is the link: http://www.metaphorandart.com/articles/trope_list.html

As I said in the first seven parts, over these several weeks, I have and will take each trope from the list and link it to a major work of art. This includes artworks from a large variety of time periods and in many different media. Generally, I am looking for artworks that embody the trope under consideration within their formal elements, clearly showing the trope in visual use. This week, Number 8:

Allegory

Generally speaking, an allegory is broader than a single trope. It is the tropaic treatment of one subject under the guise of another in a symbolical narrative or complex scene. (Although an allegory frequently uses symbols, it is different from symbolism. An allegory is a complete narrative, which involves characters, and events that stand for an abstract idea or an event. A symbol, on the other hand, is an object that stands for another object giving it a particular meaning.) Animal Farm, written by George Orwell, is an allegory that uses animals on a farm to describe political reality.

Famous allegories in literature include Edmund Spenser’s Faerie Queen, a moral and religious allegory; John Bunyan’s Pilgrim’s Progress, a Christian spiritual allegory; Herman Melville’s Moby Dick is a Modernist allegory, being one, alluding to others, and yet often subverting allegorical structure; Thomas Pynchon’s works (such as V, The Crying of Lot 49, Gravity’s Rainbow, and Vineland) are examples of Postmodernist allegory, being both highly determined allegories and yet including ambiguity and indeterminacy in their structures.

It exists likewise in comic art and literature, such as Art Spiegelman’s Maus, which uses an overtly allegorical and symbolic surface stylization to tell several densely interlocked realistic tales.

In the fine arts there has been a tradition of allegorical subject matter. Examples include Sandro Botticelli’s Primavera of c. 1482; Albrecht Dürer’s Melencolia I of 1514 (my favorite); Artemisia Gentileschi’s Allegory of Inclination of c. 1616 and her Self-Portrait as the Allegory of Painting of c. 1638–39 (perhaps my favorite self-portrait by a painter). In contemporary art there is Damien Hirst’s sculpture Verity of 2012.

Allegory often seems very old-fashioned and heavy-handed. Modernism largely rejected it in the visual arts. However, it has been resurrected in the theoretical world of Postmodernism, most famously in Craig Owen’s masterful and influential essay “The Allegorical Impulse: Toward a Theory of Postmodernism,” an article in two parts published in the journal October in 1980.1

In the spirit of embodied metaphor and my own theory of metaphor(m), I am most intrigued by works of art where the allegorical tendencies have been made flesh in the material and technical aspects of the works. Thus, yet perhaps unexpectedly, I wish to use comic artist Jack Kirby’s late-in-life autobiographical story “Street Code,” as my chief example here.2

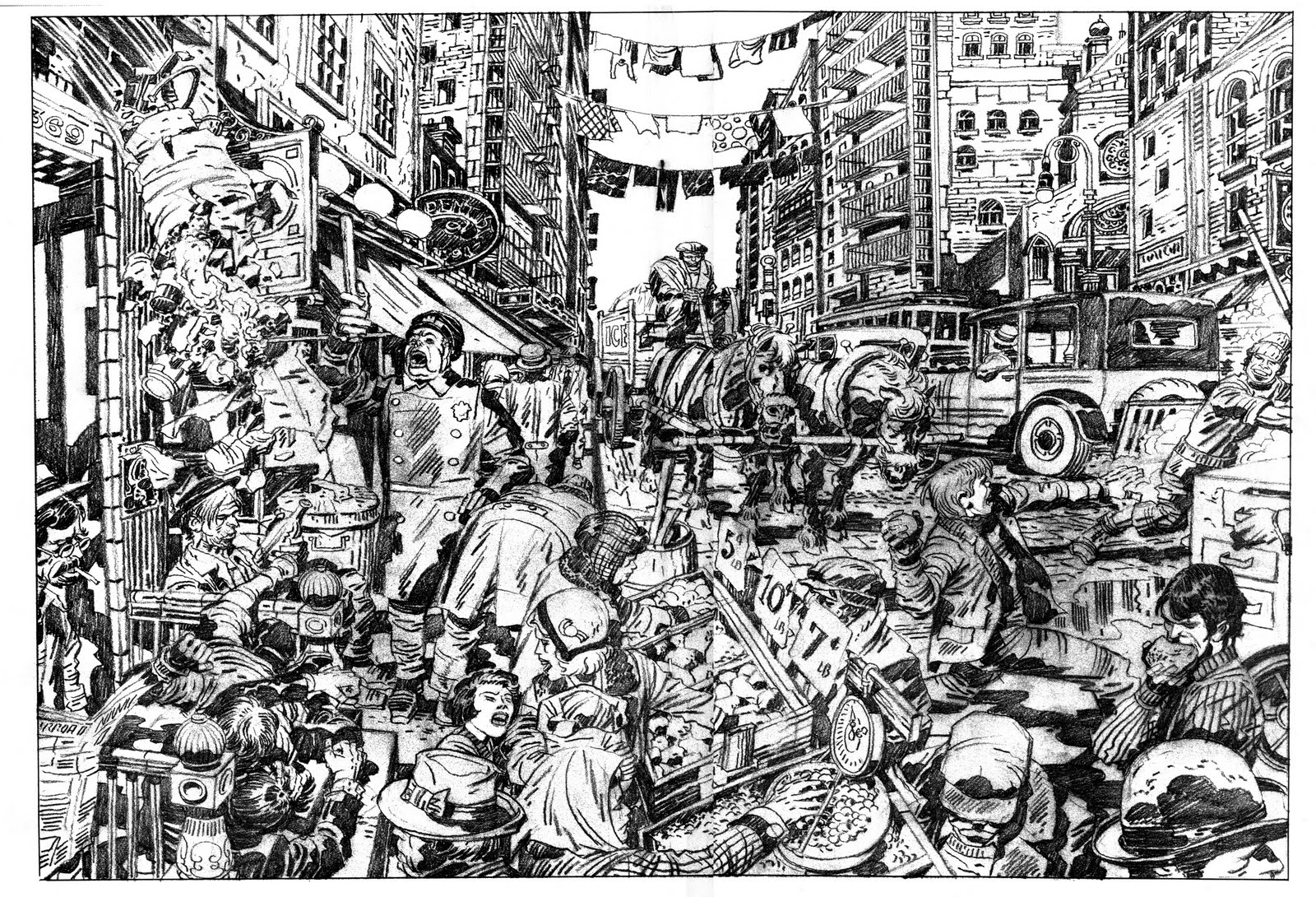

In most artworks the material, facture, composition and other technical aspects are the prime carriers of meaning, beyond the obvious referentiality of subject matter. As Barry Schwabsky has said, “The painting is not there to represent the image; the image exists in order to represent the painting. This [is] to make every painting, whether abstract or representational, into a kind of allegory of painting.”3 As Christopher Irving wrote in 2010 of the short piece of sequential art,

Jack’s childhood was a battle.

Born Jacob Kurtzberg on August 28, 1917, and given the childhood nickname Jakie, he grew up on Suffolk Street in the Lower East Side of Manhattan, in a small tenement house. Jakie, like several kids, had to work just to help keep his family fed, including hawking newspapers on the streets. He joined a street gang, the Suffolk Street Gang to be exact, and took part in street warfare with neighboring gangs.

Kirby illustrates this violent life in Street Code, illustrated in pencil in the early ’80s. As a kid, Jack fights a couple older kids in the elevator, tearing at one another’s skin as if it were rubber. Mobs of kids hoist the first throwable weapon up for an impending street fight.4

Due to the copyright issues which so plague the reproduction of comics, there is no one website with images of the whole work. Here are a few links:

http://1.bp.blogspot.com/-6WZDAJQr2hY/UD0j6CopFfI/AAAAAAAAFV4/Q2Qar8h6JSM/s1600/streetCode05-06.jpg

http://images.tcj.com/2011/05/60-SuffolkStreetGang.jpg

I can hardly due justice to the beauty and complexity of this comic in my short reference here, and that is not the point of my article anyway. Most important for my discussion at this time is that Kirby simultaneously reveals the source of and applies his life-long superhero art style to the telling of a short personal anecdote. It was printed directly from his pencilling, not inked. This was something that had seldom been done before, except in a few cases, usually with the work of artist Gene Colan. This is extremely significant for our discussion, as one sees the symbolic and allegorical aspects of Kirby’s thought focussed in the line work, detailing and composition more than in the subject matter.

In many ways, the web-like arrays of line work in this comic reminds one of Jackson Pollock, yet far more virile due to Kirby’s chunky anatomy and representations of aggression. The images are huge in spirit. When I visually remember most comic art, it appears in my thoughts at ordinary comic book panel scale. Likewise much fine art is unintentionally the small scale of an art history book reproduction. However, in this work, as in much of Kirby’s art, the drawings come into the mind’s eye as huge, mural-like explosions. His images are small in reality but immense in scale. The power is to a large extent in Kirby’s marks themselves, the potency and velocity of his pencil marks are the principal allegory in this work. When combined with the imagery from his own life, this gives us the double vector of historical understanding to Kirby’s career mentioned above. The facture, style, sense of process, even dark greyness of his marks combined into webs of expressive representation are the symbols which unite to form an emblematic narrative and multifarious scene-of-instruction (to use an anthropological term related to the study of shamanism). Allegorical metaphor(m) at its best.

Next time: Symbol